Album cover provided by Deadbeat Creative Company, Northern Ireland

What does it sound like to go bat detecting, and how can we

convey the magic of bats’ ultrasonic vocalisations through field-based

narration? We had a brief chat with Mark Ferguson—the wildlife sound recordist

behind recent Bandcamp release Walking with Bats—to find out.

Tell us a bit about yourself. How did you get into bat

detecting?

I’m a wildlife sound recordist and sound artist, with a

particular interest in the creative potential of animal vocabulary and audible

behaviours.

From 2018 to 2022, I was a doctoral researcher at the University of Birmingham, exploring how my own wildlife sounds could be used for the composition of multichannel audio works. I was doing all kinds of weird and wonderful things with sound, like placing audiences inside bumblebee nests, and drawing the sounds of bubbling water through people’s feet in the concert hall, using floor-mounted loudspeakers!

During my research in early 2020, two things happened: the COVID-19 pandemic, and the birth of my daughter. It was a very stressful time, and I had to think outside the box in order to continue recording and researching effectively. I decided to buy an ultrasound detector and teach myself as much as possible about bat detecting, absorbing well-known texts by Russ, Middleton et al., Dietz & Kiefer, etc. After learning the basics, I started heading out for short evening walks with my detector (part of my permitted daily exercise during lockdown!), making notes about my encounters and trying different recording approaches on the move. I soon became hooked, and bat detecting developed into one of my main interests as a wildlife sound recordist.

I also became a proud BCT member in 2020, and I still use the website, Bat News, BatChat and other resources to stay up to speed about bat conservation.

Bat detecting beneath an LED street light in Bristol, not far from where track 2 'Bradley Stoke' was recorded

What is Walking with Bats all about?

It’s an album of narrated wildlife walks, exploring the fascinating echolocations of UK/Irish bat species in various spots throughout south-west England and my native Northern Ireland. There are a few bonus tracks at the end, featuring some weird and wonderful extras (including a three-dimensional, software-based reconstruction of the foraging trajectory of a common pipistrelle). The main portion of the project was undertaken from April to October 2023, with a lot of work either side and support from an Arts Council England DYCP grant.

The album is my humble attempt at establishing a reference work for narrated bat detection. It’s the kind of material I hope folks will point to when someone asks, ‘What does it sound like to go bat detecting?’ It’s also been created with nature accessibility very much in mind: not everyone is able to go bat detecting, so my goal has been to transport listeners directly to the field, even if they can’t get outside or afford a bat detector.

All people need is some peace and quiet (and ideally a decent pair of headphones) to enjoy Walking with Bats.

What inspired you to undertake the project?

As a wildlife recordist who cares deeply about the natural world, I wanted to direct more positive attention towards bats, since they are so frequently misunderstood. There are so many negative associations and misconceptions about bats which need to be dismantled, and I feel that artists of all stripes need to draw more attention to just how beneficial bats are in terms of insect control, pollination, seed dispersal, ecosystem health indication, etc. Most people simply don’t realise how much bats are doing for our planet.

Looking at how people are engaging with—and learning about—other species has also been influential. On streaming platforms, we are frequently presented with camera-worthy (subjectively cute) megafauna and birds as examples of ‘wildlife’, and end up conceptualising what’s ‘worth saving’ around those images and associations. I wanted to nudge the focus firmly towards bats, since they are such exciting animals to work with and are often sidelined.

Once you take a moment to stand back and appreciate bats objectively, you start to realise just how incredible they really are.

What kind of equipment do you use for detecting bats?

I’m the proud owner of a Pettersson D1000X, which is a fantastic piece of kit. I also have a D240X as a compact, go-to detector for use on casual detecting trips.

For Walking with Bats, I found a way to mount a very small, high-quality omnidirectional microphone on top of my D1000X; this meant that I could record both my narrations and the surrounding ambience as I detected, running the microphone into a separate field recorder. I need top-level professional equipment for all of my professional audio work and research, but it’s important to emphasise that you can buy a bat detector for well under £100, or even borrow one from a local library, depending on where you are.

There are often great second-hand options, so keep your

eyes peeled on eBay! I bought my D1000X from a gentleman in Somerset, who had

had a bit of a career change and no longer needed it.

The Pettersson

D1000X, tuned to a classic heterodyne frequency of 45kHz. Rest assured that

other frequencies were used in the making of the album

If there's one thing you'd like to accomplish with Walking with Bats, what would it be

I want to make bat detecting—and the experiences around it—accessible for people, especially young people and those with disabilities.

For bat enthusiasts, detecting is already a very interesting craft and we all know why we go out in the evenings. But there’s so much to do in terms of educating the wider public about bat detecting and getting people involved; in fact, I would like to be quite bold here and suggest that we need to worry less about data gathering, and more about showing people (especially kids) just how cool bats are. We need to be working on that all the time, because as valuable as data is, it doesn’t necessarily move people to act: if data did that on its own, we would arguably be well on our way to solving the climate and biodiversity crises.

Following on from this, I think we need to be holistic with our problem solving. We need all approaches and disciplines to solve the crises we currently face as a species. We need activism and quiet persuasion and everything in between. And from my own standpoint, we especially need ongoing collaborations between artists and scientists, to get messages across and emotionally move people to act (not just inform them to).

I would argue that all of this is especially true given the

false information that has been floating around about bats during and

post-COVID. We need creative projects that highlight the beauty of bats in

interesting and engaging ways, and I hope that Walking with Bats

achieves this and inspires others to put similar projects out there.

|

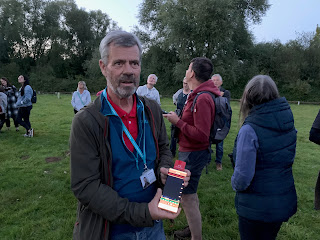

| An An evening view, during a late-summer detecting attempt around Sheepscombe, Cotswolds. Some strikingly beautiful locations were visited during recording for Walking with Bats |

Do you have any advice for young bat detectorists, or those just starting out?

It’s never been easier to get hold of a bat detector and start exploring.

One of the key messages embodied by Walking with Bats is that you really can detect anywhere: in parks, fields, suburban alleyways, even your back garden. Just go for it, and use all of the resources that BCT and other organisations have available to learn as much as you can.

Above all else, learn to listen well. The world needs good listeners who want to find out about other species and pay attention to their sounds. Bats need as much help as possible in this regard, because they aren’t normally audible to us.

We all know how important and exciting bats are; it’s time to start making their voices (and stories) heard all the clearer.

---------------------

Development of the field recording techniques used for Walking with Bats was made possible by an Arts Council England DYCP grant, awarded to Mark in 2022.

You can find out more about Mark’s work via his personalwebsite.

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(3).jpg)